The innovation: New biliary atresia program ensures faster access to treatment

Biliary atresia is a rare condition that affects newborn babies and can quickly progress to liver failure. It occurs when bile ducts become scarred, blocking the flow of bile from the liver to the small intestine and damaging the liver. But biliary atresia’s symptoms can be subtle and easy to miss. And even if a pediatrician or gastroenterologist identifies the condition in an infant, establishing a final diagnosis can be time consuming and challenging.

The hepatology team at Children’s Medical Center at Dallas and other hospital and units of Children’s Health℠ is working to overcome this challenge and advance biliary atresia care by improving and accelerating the diagnostic process, offering expertise in surgical treatment and developing the first dedicated biliary atresia program in North Texas.

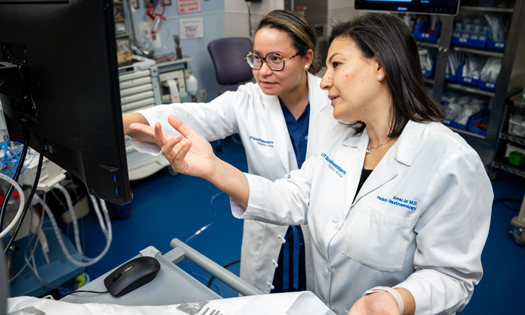

“Biliary atresia can be very serious, but if it’s diagnosed early and patients receive the right care, we can dramatically increase the likelihood that they’ll have a positive long-term outcome,” says Amal Aqul, M.D., Director of Hepatology at Children’s Health and Associate Professor at UT Southwestern. “That’s why we’re working to raise awareness of this condition among primary care doctors, and it’s why we’re doing everything we can to be sure that patients across our region have access to treatments they need.”

The big picture: Speeding the path to diagnosis

Pediatricians and gastroenterologists often carry out the initial evaluation of a baby who has jaundice, including checking bilirubin levels. High levels of bilirubin (direct or conjugated bilirubin specifically) are indicative of a serious liver condition. At this point in the evaluation, many physicians in North Texas contact the Children’s Health team.

The typical workup to definitively diagnose biliary atresia includes common and specialized blood tests and urine analysis, ultrasound and other imaging, liver biopsy, and finally an operative procedure called a cholangiogram. But experts on the hepatology team have developed ways to speed up the process, without sacrificing accuracy.

One way is a new blood test for matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7). Elevated MMP-7 has a high accuracy for biliary atresia, and results are received in just a couple of days, allowing providers and surgeons to make agile decisions about treatment.

“Two days after you send a test for MMP-7, you get the results,” says Jorge Bezerra, M.D., Pediatric Hepatologist and Pediatrician-in-Chief at Children’s Health and Professor and Chair at UT Southwestern, who led an international group that developed the MMP-7 test. “If it suggests biliary atresia, you can immediately start talking to the surgeon, make a decision about the need to perform a liver biopsy, and partner with the surgeon to take the baby to the operating room for the cholangiogram to confirm biliary atresia and perform surgical treatment.”

Children’s Health will be performing the test in-house, which allows the biliary atresia team to receive the results in only a couple of days. The Clinical Laboratory of Children’s Health will also be making this new blood test available to all physicians in the U.S.

Key Details: Developing a non-invasive definitive diagnosis

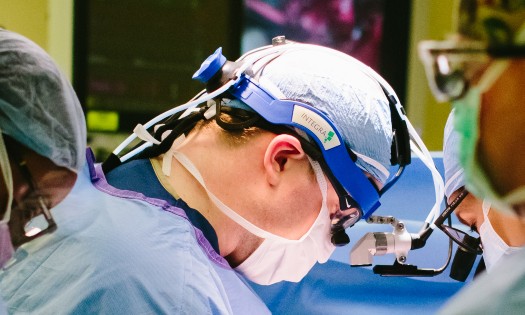

Although the cholangiogram is the gold standard test for diagnosing biliary atresia, it is invasive and complicated. The biliary atresia team is pioneering efforts to simplify the procedure, which typically involves making a moderately large incision, of about 5 centimeters, in the abdomen and injecting contrast dye into the gall bladder. Surgeons monitor the flow of the dye through all the branches of bile ducts by X-ray. If there is flow, biliary atresia can be excluded, whereas no flow means the patient has the condition – and in these cases, the surgical team performs the Kasai procedure while babies are still under anesthesia.

In 2022, Natasha Corbitt, M.D., Pediatric Surgeon and Assistant Professor at UT Southwestern, and other surgeons on the Children’s Health team replaced this approach with laparoscopic cholangiogram. It involves making 2-3 smaller incisions – totaling 7 millimeters or less – to inject the dye and view the area with a camera.

But unpublished research by Dr. Corbitt and her colleagues aims at developing a new approach to assess bile flow without using cholangiogram. The team gave a group of babies with suspected biliary atresia a fluorescent dye called indocyanine green – the same dye used for cholangiogram – intravenously. All of the babies who were confirmed not to have biliary atresia passed the dye from their liver to small intestines and pooped out the dye in their diaper. The dye could be seen simply by using a near-infrared camera, which many children’s hospitals have, Dr. Corbitt noted. In the pilot study, none of the babies with biliary atresia passed the dye because of their scarred bile ducts.

“Not having to be in the operating room and just giving that dye through an IV will help us exclude or make the diagnosis of biliary atresia a lot earlier,” Dr. Corbitt says.

Pushing ahead: Improvements in post-surgery outcomes

Diagnosing biliary atresia quickly means that surgeons can perform the Kasai procedure as early as possible. This procedure involves removing the diseased bile ducts and replacing them with small intestine tissue.

About one-third of babies will have normal liver function after the procedure, but the rest will need a liver transplant. And half of these babies will need the transplant within two years. Performing the Kasai when babies are very young – ideally less than 2 months old – increases the likelihood that they will not need a transplant, or at least not until they are older and surgery is safer, Dr. Aqul says.

Outcomes could improve with the use of therapy after the Kasai, Dr. Bezerra noted. The Children’s Health team recently started implementing a new protocol in which babies who have signs of poor liver function after the Kasai continue to receive post-operative antibiotics and corticosteroids. A study by Dr. Bezerra and colleagues that tested this protocol found that it led to babies being more likely to recover biliary drainage and keep their own liver within two years of the Kasai.

Why Children’s Health: Expertise from diagnosis to long-term care

The new Biliary Atresia Program at Children’s Health will consolidate all efforts under one umbrella and make it easier for referring providers to know exactly where to go for immediate assistance with diagnosis, treatment and management.

“We will now have a dedicated referral line for biliary atresia and we’ll be able to see patients who are referred to us within 48 hours,” Dr. Aqul says.

Children’s Health has already been caring for some of the nation’s highest volumes of biliary atresia cases. Patients receive comprehensive care from a multidisciplinary team from diagnostics through long-term care after the Kasai procedure, which includes monitoring for liver function and future complications of biliary atresia.

“We see patients regularly until they’re old enough to transition to an adult program,” Dr. Aqul says. “It’s all part of our commitment to ensuring that these patients can stay as healthy as possible and go on to live long, fulfilling lives.”